“But What if There was Equality” and Other Frivolous Gen Z Ideas

Every generation has had its platform of common thought manipulation. Our grandparents had the Radio; our parents the TV; our older siblings and cousins had the first specs of social media, and we have its ultimate form. An exploration of each can give you a great insight into what the popular ideas were for that generation, whether that be socially, economically, ethically or of course, politically. You can see where they converge and more significantly, where they diverge. And diverge they have, to say the least.

But one thing has stayed constant throughout the years, the overwhelming influence of Capitalism over the third world. Countries like Pakistan have long followed the example of their oppressors, the British, and now the Americans, hoping to emulate their successes, so one day every Pakistani could have their own American Psycho moment.

And yet, if you look closely, there is a major shift. More and more people on the younger side are playing around with, and sometimes even embracing the ideas of heathen Marx, and in a way distinct from such flirtation by generations before. This calls for an exploration: not political, but analytical. What is it that, as with other things, makes the socio-political leanings of Generation Z so different from their predecessors?

Exhaustion: A Personality Trait, not an Ailment

Not so many years ago, the peaceful greeting rise and shine turned into the hardcore ethos rise and grind, as our older millennial brothers across the world’s lives were starting to be defined by things like energy drinks and unsavory amounts of overtime.

These millennial ideals were shaped in the fires of the forge that was ‘globalization’, burning at its peak during the 90s and the 2000s, bringing promises of upward mobility with the equalizer that was interconnectivity, bringing the belief that you could computer your way straight to success. The internet was young, the potential cash from digital means seemed limitless, and the future felt something approaching secure.

Gen Z entered the foray after the hangover from the globalization party had already begun. Compared to promise, all they ever could see was competition, with thousands and millions already established before they had even started. This meant that they were already behind before they even entered the game.

This makes it not too difficult to understand that exhaustion is almost a default character trait rather than a feeling or emotion for them. Byung-Chul Han called this the ‘burnout society’, where the self-imposed drive to excel, outperform and optimize makes you drive yourself into the ground. Fatigue then is not a byproduct, but the natural state of people who have been taught from childhood that they can always do more.

(Side note: I doubt my sociology professor had me read Byung-Chul Han outside of class just so I could one day churn out another pseudo-sarcastic, borderline condescending piece about whatever’s wrong with Gen Z, but here we are, and he fits.)

Pakistan being Pakistan As Always

If you were already tired of capitalism elsewhere, thank God twice over that you weren’t born in Pakistan. Pakistan’s economy feels like that 6:30 alarm on someone else’s phone, that you’re not motivated enough to get up and stop, but not unbothered enough to fall back asleep. So, it just keeps playing and playing on loop forever.

Whether it be what feels like the eighty-fourth IMF loan, more austerity measures, rising inflation or fuel prices, nothing ever is really inspiring, to say the least. This doesn’t help when it’s the only reality you’ve ever known, growing up, and this is exactly what happened to Gen Z. Degrees don’t really mean anything when it comes to jobs (when jobs do exist that is), and even if you do get one, there’s no guarantee it’ll even be able to pay your bills.

Meanwhile, there are contradictions galore. Gated communities like the 547 DHA blocks and the Bahria towns balloon their micro-empires to what almost feels like first-world level living; artificial lakes, electrified gates and even private security. While right next door lie people who have to schedule their work around load-shedding, and flour prices define whether they can even have lunch that month or should be skipping straight to dinner.

Funnily enough, the anti-capitalist sentiment here most prominently appears not from economic frustration, but rather religio-cultural sentiment. The idea of finding blessing in sufficiency, runs against the very idea of capitalist accumulation, teaching you to be happy in what you have, for it is best for you. Anti-capitalism doesn’t appear here as an ideology, but as a way of coping with the absurdity of the system itself.

Marxism: A Novel Idea?

It might not surprise you to learn that anti-capitalist sentiment is not new in the world, not even in Pakistan. Movements such as the subtly named Communist Party of Pakistan have existed since before our grandparents learned how to say bourgeois. There was of course also the Mazdoor Kisan Party labor movements in the late 60s, the Democratic Students Federation (DSF), the NSF and so on.

But things are different now. While these movements were considered mostly niche off-shoots of off-shoots (a mouthful, but not as big as the ones the bourgeois take), nowadays anti-capitalism is actually the common trend on Tiktok. I dare you to tell me the last influencer that taught you how to leverage bonds or other financially pure income channels, yet you could probably remember three anti-9 to 5 or bad CEO memes you saw in your last scroll-session.

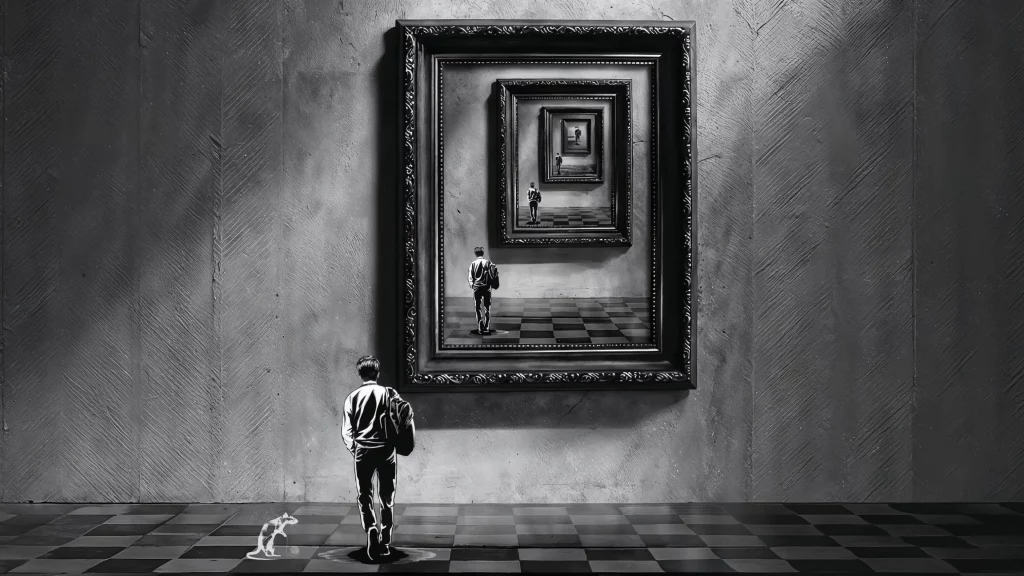

This is the real novelty of Gen Z Marxism. Anti-capitalism, once relegated to tiny red colored rallies that had trouble blocking enough traffic to be considered a minor disturbance, is now going viral as anti-work culture on social media. The language may have shifted from manifestos to 15-second video memes, but the underlying sentiments and ideas are the same. In some ways it’s actually sharper, because it doesn’t have to wear the stifling robes of ideologism; it wears relaxed-fit jeans.

Linking Marxism to the Brainrot Generation

How upfront Gen Z might be in calling themselves ‘Marxist’ is debatable (this is a generation that despises labels, after all), but to deny their marxist sentimentality and instincts would be naive. The average 20-something isn’t reading Das Kapital on a Friday night, but they don’t need to. Their politics lives in that gut feeling, that reflexive annoyance that bubbles to the surface every time a billionaire tweets about ‘hard work’, or when yet another company posts record profits…after their most recent round of layoffs.

This is Marxism memefied. You don’t need to explain class antagonism to a generation that made ‘Eat the Rich’ a part of pop culture. Who says they don’t know the term surplus value when they know all the trending reel formats talking about CEO’s buying yachts while they’re struggling to buy their packet of M&M’s?

And yet, it’s not just jokes. Underneath the brainrot humor lies a growing hostility to the upper class and its (modern) symbols: the property dealer on insta showing houses that cost as much as a small country, the influencer who flaunts luxury bags right after her post about saving water, the DHA uncle bragging about his latest imported SUV. The critique isn’t always dressed in manifestos, it often looks like sarcasm, side-eye, or satire. But it carries the same charge Marx pointed to long ago: the suspicion that the system is designed to enrich a few at the expense of the many.

In other words, the revolution isn’t televised. It’s shitposted.

Electric Cars Accelerate Faster than Gas Cars

But why is social media so much better as a viral disease carrier than all the mediums before it? We can surmise it to be a combination of a few things.

First, the format. Tiktok, tweets and memes are all bite-sized information conveyances; easily digestible critiques of hustle culture and the upper class elites, brought right to your bedroom. A joke about Jeffrey Bezos will reach more people in a week than a 30-page economic paper ever could or did. And the best part? No background reading required.

Second is of course, aesthetics; the modern-day form of peer-pressure, if you will. When you promote cottagecore and endless streams of anti-9 to 5 humor, you’re packaging resistance as lifestyle. And all one has to do is get it trending to make it so that the overwhelming majority adopt it.

And third is, as mentioned before, globalization. The fact that I, sitting in a third world country in the middle of South Asia, could learn within minutes about rent strikes in London or the housing crisis in New York, allows me to not just draw parallels, but learn from the source how to best mobilize.

The sociology here is simple: emotions (anger, annoyance, humor) spread ideas much faster than academics. Marx had pamphlets, we have Wi-Fi.

I also Desire ‘The Good Life’, but Not Yours

So where does this land us in practice? For eons, capitalism has sold a singular promise of what it describes as The Good Life: happiness through the accumulation of wealth (and subsequently material pleasures). A good house, a good car, maybe a yearly vacation to Murree. I mean, that’s all my parents ever cared about.

But Gen Z sees the economic stagnation and climate collapse, and sees nothing but a lie wrapped in shiny promises. From all they can see, the only definite result the pursuit of wealth leads to is burnout, alienation and an endless moving of the goalposts.

Because of this, a new definition of the good life is emerging. Now, it’s about leisure held in equal weight to work. It’s about peace and mental health kept in just as high regard as that extra hour of overtime, enough so that the yearning for the former might just overpower the greed for the latter. Terms like dignity are being used alongside casual labels like corporate slave (i personally prefer corporate majdoor).

Connection is a big part. Durkheim explained it as anomie; the phenomenon of a feeling of disconnection arising from the normlessness of society. When society is always changing and evolving, there is nothing to stay put with, leading to a loss of social cohesion. The increased emphasis on prioritizing your friends as an ideal emerged as Gen Z counter to this feeling.

So What Do These Stinking Kids Want?

While Millennials chased the old milestones: cars, houses and jobs in bougie offices; Gen Z has no illusions of these being within their reach, or even worth chasing. Their desires are much more pared down, but not in a defeatist way, just a more pragmatic one. They want balance, mobility, dignity and work that is fulfilling.

The dream of ‘rich’ has been replaced with the dream of ‘enough’. Enough to live peacefully, and enough to indulge their hobbies. Enough to be free of debt, and enough to care for their loved ones.

This doesn’t mean that money doesn’t matter to Gen Z, just that they are grossly against hoarding it. They’d much rather the rest be used for the benefit of everyone. There’s this climate change thing they saw a podcast about, why not spend some cash on fixing that? How about housing for those that can’t afford it? Healthcare even?

I don’t have to underline the clear Marxist ideals in these desires for you to see how prominently they pop up. Where older generations asked, “How can I climb higher?” Gen Z asks, “How can I step off the ladder altogether?”.

But Does It Even Matter?

“I studied science so my son could study art”. But his son will probably have to study science again, so they’re not on the streets dirt poor with nothing to their name but weeabo paintings.

That’s the tension point at the heart of Gen Z’s ideological shift. While their rejection of traditional capitalism is notable, the bulk of its expression stays online. Sharing a TikTok about evil landlords or posting anti-work humor might create social connection and maybe even solidarity, but it rarely seems to translate to union drives, strikes or organized political action in most cases.

Virality, paradoxically follows a repeating pattern: outrage peaks quickly, and then dies down, reaching a point as if nothing ever even happened. The loop recurs every single week in trend culture. But while momentarily the world feels like revolution, sustaining momentum in the physical world requires a lot more than a heart emoji.

Still, ideas are ideas, and ideas have a way of acting as a seed. While critiques might feel fleeting, they are undeniably shifting the cultural baseline. What one generation rants about, the next may institutionalize. Maybe not this generation, but their children, or their grandchildren, might have the proactiveness to turn ideology into constant, structural change.

In Closing: A Value Proposition

At its core, this isn’t just another version of left versus right. It’s not even about politics. The real question Gen Z keeps forcing onto the table is deceptively simple: what does it mean to have a good life?

For some, the answer used to be accumulation, whether cash, assets or prestige. But for many younger people today, that answer seems to ring hollow. They are asking out-of-syllabus follow-up questions: is that really worth the trade of time, energy and sanity?

That is why their Marxist leaning feels less like ideology and more like necessity. It’s not a manifesto, it’s survival. When the promised ‘good life’ is unreachable, Gen Z moves forward. Now what we look for is balance, dignity, and community.

So I suppose we all just need to ask ourselves a few questions: What does it mean to live a good life? What is enough? And maybe most importantly, what is worth working for?