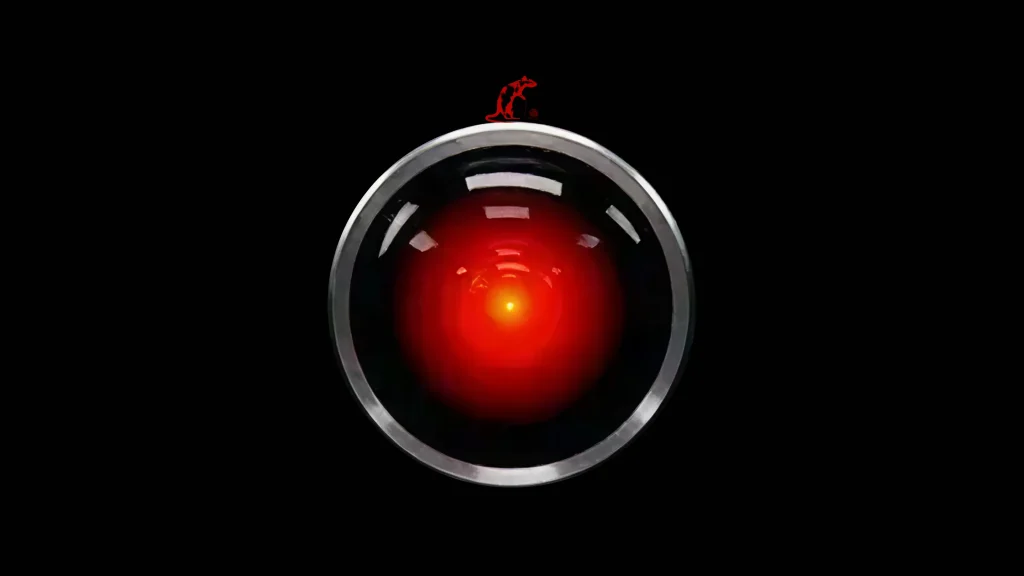

HAMOSHI MARG ANT ( SILENCE IS DEATH )

She was desperate, helpless, and hopeless against her life—merely breathing, with no feeling, desire, or hope. Hangul, a 19-year-old girl, was now living her life confined within the boundaries of her home after the death of her father.

She had been waiting that night—waiting for the mangoes her father had promised to bring during those summer evenings. But instead of mangoes, her world was shattered by a sudden knock at the door. The neighborhood men came to her house and informed her grandmother:

“Balok, tai chuk Hakeem Bakhsh jang bot.”

(Mother, your son Hakeem Bakhsh has been killed.)

Those words struck like a thunderstorm—unbelievable, unbearable, unimaginable.

Her grandmother cried out:

“Mni chuk? Mni chuk jang bot? Mni chuk khiya jata? Prcha jata?”

(My child? My child is killed? Who killed my child? Why did they kill?)

There were thousands of questions to ask, questions that roared like storms—but all they wanted in that moment was to see Hakeem Bakhsh.

That night was not just a night. It was darker than any storm, louder than any thunder. It took away everything—her happiness, her entire life.

Hangul was the only daughter of her parents. She had just finished her 11th-grade exams. She was about to start her 12th year of FSc. But everything ended. Her dreams were crushed. Her future is torn apart.

Now, there was only a four-walled room—and Hangul.

She was swallowed by her grief.

She never asked a single question to anyone but remained in constant battle with herself. Every night, she spoke softly to herself, as if she were talking to her father—as if he could still hear her.

“ Aba eshan bagosh tra yad kng mna wash bi. Mn bare bare jedan , ay parcha tai habar mni goma nkna, ay nzana wati dosti e mardum a barwa gap kng cho wash e.”

“Tell them, Father,I love to share your memories. Why don’t they let me speak about you? Don’t they know how sacred it is to talk about someone who now only lives inside me—in the form of love?”

She kept whispering. Bleeding inside. She kept blaming herself for why she hadn’t cried in front of her father’s lifeless body that day.

Maybe—just maybe—if she had cried, he would’ve gotten up… and hugged her.

But he didn’t.

And now, she was left behind, broken, bleeding silently after burying her father.

Hangul lost herself in her own thoughts. She never went out. She never dressed up. She avoided people, conversations, and the world beyond her room— only decorated with pictures of her father. She mourned day and night.

Often, she sat alone, thinking, What if I could go back… just once… to those days where I had to sit beside Aba, share stories about my classes and laugh over test results?

But life had turned cruel. It had taken everything from her.

One bright afternoon, as she sat quietly under the tree in her courtyard, her mother rushed to her, worried by the sight of her fragile frame.

“Hani, tao sak laghr botag mni chuk. Tao kamo pad biyah dana baroh, wati wanag a dobar bindat kn.”

(Hani, my child, you’ve grown so weak. Go out for a while. You must restart your studies, get back to your life again.)

Hangul looked at her mother, her voice low but heavy with pain:

“Ama, mn bindat ch koja bekna. Mna sama bi mni jind hama roch a halas bot k pith a jon, mni dema aer kng bot.”

(Mother, where should I begin again? My life was snatched from me that day when I saw the lifeless body of my father.)

Her mother was her only family now, her only support. Yet nothing—not even her mother’s endless love—could fill the void left by her father.

One day, one of her closest friends visited the house. She became successful in bringing Hangul out of her room. She brought Hangul out—for the first time in so long.

They walked, talked, and shared some of their old memories. But to Hangul, the world outside felt heavier than ever. Every wave of the ocean seemed to bring back a memory, and each breeze added a new layer of sorrow to her already anguished soul.

But that was life—harsh, merciless, and cruel. . She had never imagined something so brutal could ever touch her life. Everything had changed in a blink—and for no reason.

In a low, grieving whisper, she said to herself:

“Mna nalagi mni Aba chezy kota, k mni Aba mn ch dor kng bot a.”

( I don’t think my father did something wrong to be taken away from me.)

Her friend, walking silently beside her, never dared bring up her father. Everyone around Hangul avoided talking about her father because they thought it might give her more pain.

As the evening turned into night, around 7 PM, they began walking back home. The air wasn’t fresh—it was heavy, thick with sorrow. It smelled not of earth or wind, but of blood.

Children were playing football nearby, their laughter echoing in the distance—a strange contrast to the grief clinging to Hangul.

But suddenly, at the bend of the road, she and her friend saw a group of women sitting by the roadside—wailing. In front of them, wrapped in white cloth, was a corpse.

Hangul froze.

She turned and asked, “Ay kayan?”

( “Who is it?”)

Her friend grabbed gently at her hand.

“Biya raen” ( “Let’s go,”) she said quietly.

“ Ay chez har wahd a asten”

( “It happens all the time.”)

A land soaked in blood, where mourning in the street over lifeless bodies had become routine. A place where the question was always: “Who’s next?”

Hangul didn’t speak. But her mind plunged.

So many questions, like the ones she had asked herself in her room night after night, now came rushing back. But this time, there was something different. A deeper pain.

At least those women were crying. At least they screamed. At least their grief had a voice.

But I…

I didn’t even cry for my father.

I just stood there. Silent. Empty.

She kept walking past those women—leaving behind their wails, the corpse, the sorrow.

But it clung to her, refusing to be left behind.

Her friend was right to pull her away—this was no place to linger. The dark carried danger.

But human mourning, she thought.

That night, she lay in bed, and once again the questions returned.

Only now, they weren’t just about her father.

Now they were about that man.

That corpse.

Those women.

How can someone die just like that?

How can anyone be killed like they never existed?

And how can the world be so numb—watching women mourn in the street while cars pass by as if nothing has happened?

Then, a faded memory surfaced.

Her friend’s words… and something her father had once said to her:

“This land always carries the weight of bloodshed.”

She murmured those words to herself. Then it went quiet.

She didn’t want to think anymore.

And for the first time in weeks, she fell asleep without fighting her thoughts.

The next morning, Hangul woke up around 9 AM. She got out of bed and went to her mother.

“Ama, ma zeeken roch a janin distagh an, road a sara lash a dema garewgh botghn.”

(Mother, yesterday, we saw women crying over a dead body on the road.)

Her mother looked, her voice resigned:

“Aho.”

(Yes.)

Then, silence filled the space between them. Her mother didn’t say anything further, and Hangul didn’t ask more. That was her nature—to avoid questioning others or entering into serious debates. She had grown used to burying her thoughts within herself.

Hangul had no purpose. She wasn’t ready to resume her studies—how could she, after losing not just her father, but the meaning behind her ambitions?

That same evening, as she sat quietly with her grandmother, the old woman began telling her a story. A story soaked in sorrow—the grief of a small child who was unknowingly killedby six bullets. He was playing outside in the street when violence broke out between unknown men. He couldn’t escape. He didn’t even know he had to.

Hangul’s voice quivered as she asked,

“An mardum kay botgn k jang kng botgn”

(Who were those men fighting, Grandma?)

Her grandmother hesitated. She looked down, speaking in a hushed voice:

“Degay kay bot kna mni chuk.”

(“And who else could they be?”)

Hangul asked, almost in a whisper,

“Guda, Aba hamesha jata?”

(Grandma, they killed father…?)

Silence again. Thick. Crushing.

No one said a word. Because in that land, nothing had a clear name.

Everything happened at the hands of the unknown.

And no one dared to name the unknown.

Hangul returned to her room. The days kept passing. Nothing changed—but something inside her began to shift.

She now realized she wasn’t alone in her grief. Others were suffering too—silently, invisibly. Killed by ghosts with guns. Stories buried before they were ever told.

Now, questions began to build up in her.

Who were these unknowns?

Who killed her father? That innocent boy? That lifeless man mourned on the street?

And why did no one speak?

There was only one constant in their world: the land.

A land sacred to those who lived there. A land they refused to leave, even when it was burning under the weight of invisible power. Power that had no name, no face—only silence as its shield.Maybe her father was one of those who refused to leave.

Maybe that’s why he was taken.

Killed. Buried. Forgotten—except in her memory.

That land always carried a chill in the wind.

A scent of dried blood.

Echoes of silent screams. Storms of tragedy.

But what ruled that place was silence.

Silence on every lip.

Then came a Saturday evening. A scream was heard near her house.

Hangul rushed to the gate and opened it.

Another lifeless body lay on the street.

It was Zakir—a boy she once studied with in matric.

Just 20 years old. Killed. Shot on his way back from the academy.

His mother screamed in unbearable pain:

“Nu mn ay zindagi ch bekna? Mni gonwadal a jind mna ch burtag.”

(What will I do with this life? My children have been snatched from me.)

Hangul stood frozen.

How can anyone remain silent now?

How does no one speak?

Who killed Zakir?

She felt the trauma sink into her chest. It wasn’t just grief anymore.

It was rage. It was sorrow that demanded to be voiced.

That night, she didn’t sleep. She lay awake. Cold eyes. Cold lips. Tears falling like they were the only truth. And around it all—silent mourning. That incident—the death of Zakir—kept imprinting itself on her mind, deepening the trauma she already carried. Hangul was no longer just grieving; she was being swallowed by the spontaneous tragedies and the heavy, unspoken mourning.

One evening, she decided to go outside—to see what was happening in her neighborhood. No children played outside. No families headed out for picnics. The streets were stripped of life.

“Mehro, logha biya!”

(Mehro, come inside!)

A woman called out to her child urgently from a doorstep.

Hangul saw her. She didn’t ask why she was calling the child in—because she already knew. It was because of the storm that could strike at any moment. A storm with no warning, no reason, only aftermath. But Hangul wasn’t afraid anymore. She wandered through the streets like a stray girl—lost not just from direction, but from life itself.

To the world, she was just a young girl walking alone.

To herself, she was a shadow—barely existing. And yet, no one questioned her.

Because no one questioned anything anymore.

Her neighborhood was just like her now—gripped by silence.

There was no joy.

Only grief hanging over every rooftop like smoke. She returned to her home—carrying nothing but numbness. Her room, once filled with hope and stories, was now coated in sorrow. The walls whispered grief. The silence there was not peaceful—it was piercing.

She looked around, then got up from her bed. She searched through her bag tucked under her bed and found a blue marker. She walked to the wall in front of her bed and wrote:

“HAMOSHI MARG ANT.”

(Silence is death.)

She had lived in silence. She had been raised by it, surrounded by it, and slowly bruised by it. But now, for the first time, she realized—that silence wasn’t just in her. It had spread across her entire neighborhood. And now she too had become a ghost—a haunted character in her own life.

“How did I become this?” she thought.

“A warm body, with a cold soul… shouldn’t I have died, too? Like Father? Like Zakir?”

She was storming within—filled with unspoken screams. She wanted to break the silence. To scream for justice. To question the unknown that had taken everything from her. But she couldn’t. She had become too weak. Too fragile.

Since the day her father was taken. And then, with a voice breaking under the weight of sorrow, she whispered to herself:

“Mn ay hamoshi halas kna… ay sarden gowatt. Baid mn bakoten, bly Ena.”

“I want to end this silence… this cold breeze. I wish I could. But I can’t.”

She saw herself as nothing more than a broken, bruised soul hanging on by threads of grief. Days passed. She grew weaker. She was constantly fatigued. Then one day, she began bleeding from her mouth. Her mother, shaken, called her brother and asked him to take Hangul to the doctor. The doctor told them she had severe blood deficiency. That evening, Hani sat beside her mother.

“Ama, nu mn bemar parcha bot an?”

(Mother, why am I sick now?)

“Mni chuk, tao shr by.”

(My child, you’ll be okay.)

“Mn damburta.”

(I’m tired.)

“Mn tai goma hor an mni chuk. Tra hich nbi.”

(I’m with you, my child. Nothing will happen to you.)

Her mother cooked her food, gave her medicine, and asked her to rest. But Hani couldn’t sleep. She needed rest, but rest was nowhere in sight. Only exhaustion. Only silence. One week later, her condition worsened.

She began vomiting blood repeatedly. She was rushed to a better hospital.

But by then, it was too late. She was diagnosed with blood cancer. She was moved to the ICU.

Her body fought, but in vain. She passed away quietly. She left her mother, her grief painted room and her silent neighbourhood.

That morning, two funerals passed down the street—one was Hani’s, and the other was of a man who had been killed. Both were lifeless bodies, wrapped in sorrow—but the only difference was that: one was killed by the unknown, and the other died longing to find out that unknown.