Sklavenmoral vs Sabar

A father in Gaza wakes up to the sound of drones. The city, once alive, is now a graveyard of memories. His home is rubble, his livelihood shattered. He walks past lifeless bodies, past children who have known nothing but war. Aid is scarce, the world indifferent. What do you say if he asks you the following: Is patience in the face of oppression a virtue, or is it cowardice? Should I endure, or should I resist?

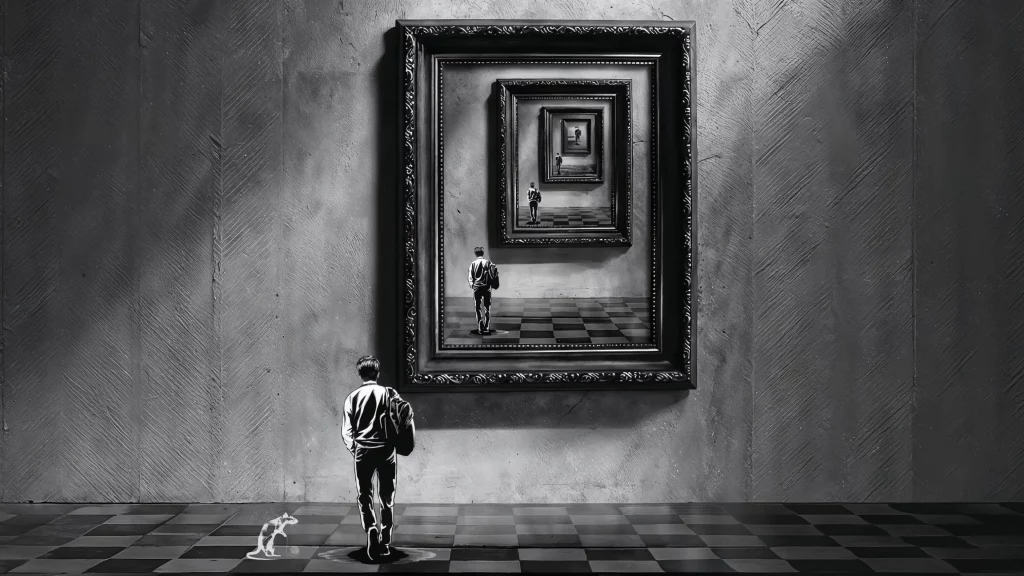

This question—between endurance and defiance—lies at the heart of moral deliberation. Two opposing frameworks emerge: Friedrich Nietzsche’s critique of “slave morality” and the Islamic concept of sabr (patience). For Nietzsche, endurance is submission; for Islam, patience is an act of strength. To grasp this tension, we must first turn to Nietzsche’s moral genealogy.

Sklavenmoral and the Illusion of Virtue can also be understood this way.

In On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche exposes what he sees as the deception of traditional morality. Strength, power, and self-assertion—once valued in Herrenmoral (master morality)—are inverted by the weak, who redefine their impotence as virtue. The slave, unable to change his reality, consoles himself with values like humility and patience. This, Nietzsche argues, is ressentiment: a psychological inversion where the oppressed find solace in their suffering instead of overcoming it.

“The miserable alone are the good; those who suffer and are oppressed are the only pious ones, those who are in need, the sick, and the ugly are the only blessed by God; but you, you noble and mighty ones, you are for all eternity the evil, the cruel, the lustful, the insatiable, the godless, you will also be eternally the wretched, cursed and damned!” (First Essay, §13)

Nietzsche traces this inversion primarily to Christianity, which, in his view, exalts weakness and suffering as virtues while vilifying strength, dominance, and self-assertion. The Christian moral framework, he argues, is built upon a fundamental revaluation of values—one that elevates meekness, humility, and submission while condemning pride, power, and vitality. The meek are declared blessed, the poor are promised the kingdom of heaven, and suffering is sacralized as a path to redemption. The ultimate reward for endurance and obedience is not found in this world but in an afterlife, a metaphysical compensation that justifies submission to oppression.

Nietzsche sees this as an elaborate rationalization, self-deception that allows the weak to cope with their inability to impose their will upon the world. Rather than confronting life’s harsh realities, they construct a moral system that frames their own powerlessness as righteousness. This, he argues, is the essence of ressentiment: the psychological mechanism through which the weak, unable to act, redefine their inability as moral superiority. Slave morality is not a genuine ethical system but a doctrine of inaction masquerading as virtue, a means by which the powerless console themselves while subtly seeking to undermine those who possess strength and vitality. In this way, Nietzsche contends, traditional morality is not an affirmation of life but a reaction against it.

But is all patience a form of submission? Does endurance always entail resignation?

Islamic sabr is not passive endurance. It is resilience, a conscious defiance against despair. The Quranic command fasbir sabran jameela—“endure with a beautiful patience” (70:5)—does not mean acceptance of oppression. It means endurance with dignity, without surrendering to nihilism or hatred.

Unlike Nietzsche’s slave morality, which stems from resentment, sabr stems from conviction. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ did not endure hardship with passivity—he endured while struggling against oppression. The endurance of Musa (AS) against Pharaoh, the patience of the people of Mecca under torture—these are not examples of submission but of principled steadfastness.

Western philosophy often equates patience with either weakness (Nietzsche) or delayed gratification (Kant). Islam reframes it as a metaphysical force. Mulla Sadra’s concept of al-haraka al-jawhariyya (substantial motion) sees the soul as constantly evolving. Through struggle and endurance, one transcends suffering—not by ignoring it, but by transforming it into a path toward the divine.

Nietzsche’s Übermensch rejects moral constraints and seeks to impose his will upon the world. But Islam offers an alternative: true strength is not found in domination but in self-mastery. The father in Gaza who endures with faith does not submit—he transcends. His patience is not passivity but resistance, not resignation but conviction.

The true victor is not the one who overcomes others, but the one who overcomes himself. In this, sabr is not a relic of slave morality but a force of transformation, beyond Nietzsche’s grasp.